FIG PUBLICATION NO. 52

The Social Tenure Domain Model

A Pro-Poor Land Tool

Christiaan Lemmen

INTERNATIONAL FEDERATION

OF SURVEYORS (FIG) |

UNITED NATIONS HUMAN SETTLEMENTS

PROGRAMME (UN-HABITAT) |

GLOBAL LAND TOOL NETWORK

(GLTN) |

This publication in other languages (pdf):

Contents

Foreword

1. Introduction

2. The Need for STDM: Identifying the Gap

3. The STDM Tool: Closing the Gap

4. The Benefit of STDM: Support in Sustainable

Development

5. The Use: Simple Approach, Unconventional

Transactions

6. The Process: Developing the STDM

Further Reading

Orders for printed copies

Most developing countries have less than 30 percent cadastral coverage.

This means that over 70 percent of the land in many countries is generally

outside the land register. This has caused enormous problems for example in

cities, where over one billion people live in slums without proper water,

sanitation, community facilities, security of tenure or quality of life.

This has also caused problems for countries with regard to food security and

rural land management issues.

The Global Land Tool Network (GLTN), facilitated by UN-HABITAT and funded by

Norway and Sweden, is a coalition of international partners, including FIG (the

International Federation of Surveyors), ITC (University of Twente, Faculty of

Geo-information Science and Earth Observation, The Netherlands), and the World

Bank (WB), has taken up this challenge and is supporting the development of

pro-poor land management tools, to address the technical gaps associated with

unregistered land, the upgrading of slums, and urban and rural land management.

The security of tenure of people in these areas relies on forms of tenure

different from individual free hold. Most off register rights and claims are

based on social tenures. GLTN partners support a continuum of land rights, which

include rights that are documented as well as undocumented, from individuals and

groups, from pastoralist, and in slums which are legal as well as illegal and

informal.

This range of rights generally cannot be described relative to a parcel, and

therefore new forms of spatial units are needed. A model has been developed to

accommodate these social tenures, termed the Social Tenure Domain Model (STDM).

A first prototype of STDM is available. This is a pro-poor land information

management system that can be used to support the land administration of the

poor in urban and rural areas, which can also be linked to the cadastral system

in order that all information can be integrated.

The chair of Working Group 7.1 of Commission 7 on Cadastre and Land

Management, Christiaan Lemmen, took the lead from 2002 onwards, in the

development of the STDM in close co-operation with UN-HABITAT. ITC, financially

supported by the GLTN, developed a first prototype of STDM, that is supported by

WB.

This FIG Report presents the need for STDM, the properties of STDM as a tool,

and the benefit and use of STDM as a key means of meeting the Millennium

Development Goals (MDGs).

Prof. Stig Enemark

FIG President |

Dr. Clarissa Augustinus

Chief, Land and Tenure Section

Global Division, UN-HABITAT |

1. Introduction

Land Administration Systems (LAS) provide the infrastructure for

implementation of land polices and land management strategies in support of

sustainable development. The infrastructure includes institutional arrangements,

a legal framework, processes, standards, land information, management and

dissemination systems, and technologies required to support allocation, land

markets, valuation, control of use, and development of interests in land.

In many countries such infrastructure is not available with a nationwide

coverage. In fact this is the case in only 25 to 30 countries worldwide. Further

it can be observed that existing LAS have limitations because of the fact that

informal and customary tenures cannot be included in these registrations.

Generally, the Land Administration Systems are not designed for this purpose.

Existing LAS require extensions to include all existing types of tenures. But

the need for this is not always recognised and institutional changes are not so

easy to implement.

The Social Tenure Domain Model (STDM) could close this gap: STDM allows for

the recordation of all possible types of tenures; STDM enables to show what can

be observed on the ground in terms of tenure as agreed within local communities.

This agreement counts as evidence from the field.

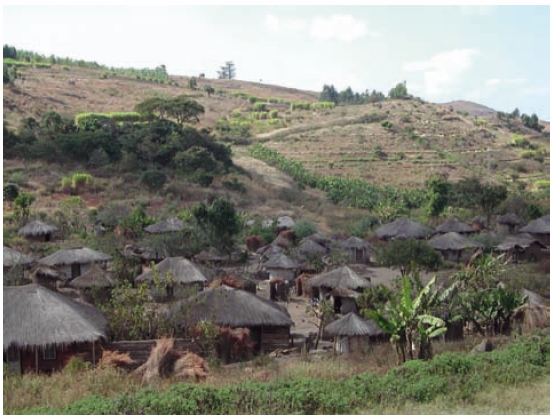

People, living in informal area’s in developing countries, who are visited by

someone with an enlarged satellite image or aerial photo in his or her hands

will give attention to this image or photo. The visitor will be surrounded by

many people almost immediately.

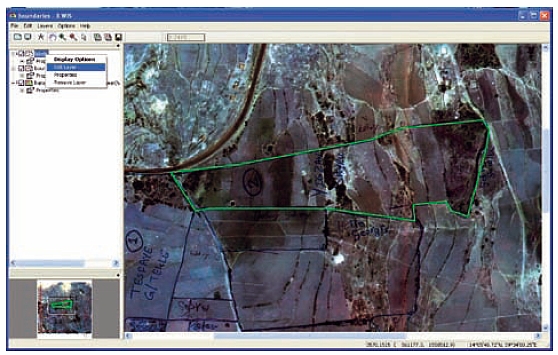

People really understand what they see on the image. They can identify the

place where they live, and where their neighbours live. See Figure 1.

Figure 1: Satellite imagery as basis for data collection. People

recognise immediately the roads and spatial units on the images. High resolution

images can be enlarged and printed with overlaps with ‘neighbour prints’. Based

on the identification of boundaries on the images the boundaries can be drawn on

the image. © Christiaan Lemmen

Surveyors as land professionals are needed in support and management of this

type of data acquisition of ‘people – land’ relationships. This is asking for

widening the scope in relation to land administration; apart from traditional

field surveys related to formal tenure there can be a context as described for

informal tenures. Surveyors understand that there can be differences in spatial

accuracies resulting in different accuracy quality labels. Surveyors can not

only provide accurate maps but they also know how accurate the map is or should

be for the purpose. And surveyors have experience in land administration based

on observations on site.

UN-HABITAT, with support of FIG and WB, developed STDM into a first

prototype, based on an open source database with open GIS software, in close

cooperation with ITC. FIG and UN-HABITAT are involved in the development of an

ISO-standard for a land administration domain model (LADM), including the STDM1).

As soon as this ISO-standard is available it can be used by open source

communities and by commercial software integrators to develop Land

Administration Systems. The ISO-standard can be adapted and extended for local

purposes and avoids reinventing the wheel.

Customary tenure areas are normally outside the formal land registration system.

Malawi. © Stig Enemark

1) The LADM is under development within the Technical

Committee 211 (TC211) of the International Organization for Standardization

(ISO) and identified as ISO 19152. FIG took the initiative for this standardised

domain model for the Land Administration Domain. UN-HABITAT is involved in this

development. This International standard is expected to be available in 2011.

2. The Need for STDM: Identifying the Gap

There is a gap in conventional land administration systems: customary

and informal tenure cannot be handled. There is a need for unconventional

approaches in land administration.

Where there is little land information, there is little or no land

management. Conventional Land Administration Systems are based on the ‘parcel

approach’ as applied in the developed world and implemented in developing

countries in colonial times. A more flexible system is needed for identifying

the various kinds of land tenure in informal settlements or in customary areas.

Traditional land surveys are costly and time consuming. For this reason

alternatives are needed; e.g. boundary surveys based on handheld GPS

observations, or by drawing boundaries on satellite images. This means of course

a different accuracy of co-ordinates. Surveyors understand this and surveyors

are needed to provide quality labels and to improve the quality of co-ordinates

at a later moment in time.

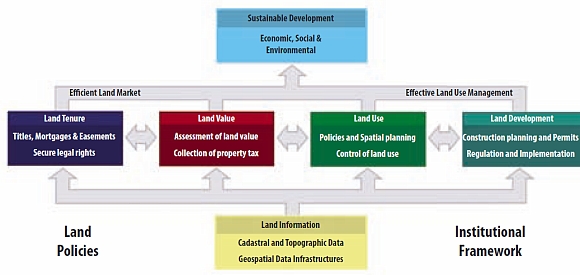

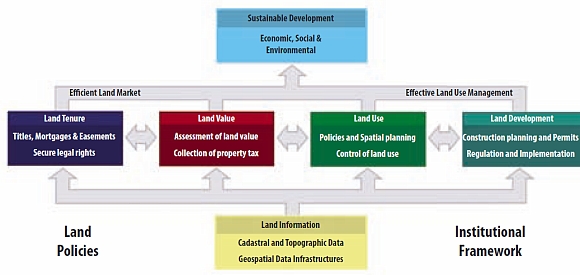

The need for a complete coverage of all land by LAS is urgent. Not only for

the registration of formal rights and for the recordation of informal and

customary rights. Also for managing the value, the use of land and land

development plans. This relates to Enemark’s model on the global land management

perspective; see Figure 2. Complete coverage of all land in a Land

Administration is only possible with an extendable and flexible model, that

enables inclusion of all land and all people within the four land administration

functions. So STDM will close part of the technical gap in developing countries

in terms of making Land Administration covering the total territory.

Impact of disasters, like the 2010 earth quake in Haiti, are difficult to

manage because it is not clear which lands are available for people to be

temporally resettled in tents. After the 2004 tsunami there was land grabbing

where owners had passed away. It is also known that children of parents having

aids lost their living place after parents had passed away.

It is astonishing that interventions in the daily life of communities by

mining industries, by mega farming, or by deforestation are awarded by

governments with land titles, while the rights of local communities are not

recognised. At the same time local communities discriminate women, where access

to land is concerned, in contradiction to national land policies. Given today’s

problems related to urbanisation, environment, access to land, and access to

food and water there is a need to get a complete overview of who is living

where, under which tenure conditions, and for which areas. Overlapping claims to

land need to be included as well as Illegal acquisition or occupation of land. A

complete map of ‘people – land’ relationships is needed.

Such a more flexible extension of LAS should be based on a global standard

and should be manageable by local communities them self from the start.

Standardisation allows for integration of data collected by communities into

formal LAS at a later moment in time.

It should not be misunderstood that formal land titling is important and

necessary, but it is not enough on its own to deliver security of tenure to the

majority of citizens in most developing counties. Customary tenure and informal

settlement tenure have a very strong influence. Individual land titling often

works against the needs and aspirations of poor people, also because of its

cost. Rich landholders are often against land titling because it will visualise

the areas which may be grabbed. Or they may be interested in which areas are not

in the official system, thereby knowing which areas are available for land

grabbing.

Land administration comprises an extensive range of systems and

processes to manage:

- Land tenure: the allocation and security of rights in

lands; the legal or informal surveys to determine boundaries of

spatial units; the transfer of formal or informal rights or use

from one party to another through sale or lease; and the

management and adjudication of doubts and disputes regarding

social tenure relationships and boundaries.

- Land value: the assessment of the value of land and

properties; the gathering of revenues through taxation; and the

management and adjudication of land valuation and taxation

disputes.

- Land use: the control of land use through the

adoption of planning policies and land use regulations at

national, regional and local levels; the enforcement of land use

regulations; and the management and adjudication of land use

conflicts.

- Land development: the building of new physical

infrastructure; the implementation of construction planning and

change of land use through planning permission and the granting

of permits.

Inevitably, all four functions are interrelated. The

interrelations appear because the conceptual, economic, and physical

uses of land and properties serve as an influence on land values.

Land values are also influenced by the possible future use of land

determined through zoning, land-use planning regulations, and

permitgranting processes. And land-use planning and policies will,

of course, determine and regulate future land development.

Land information should be organized to combine cadastral and

topographic data and to link the built environment (including legal

and social land rights) with the natural environment (including

topographical, environmental, and natural resource issues).

(Williamson, Enemark, Wallace, Rajabifard, 2010) |

Figure 2:

Land Administration Systems provide the infrastructure for

implementation of land polices and land management strategies in support of

sustainable development.

In many countries the land rights of people and legal entities are documented

in a land register and the parcels and their boundaries are recorded in a

cadastre. Sometimes those organisations are under one umbrella. Conveyancers and

land surveyors are in support of adjudication and maintenance processes. Mostly

there is no ‘one-stop-shop’ service in transactions of land rights. Citizens

have to compensate costs for transactions which often lead to corruption. This

makes land administration not a popular activity in many countries. People

should have the confidence that land administration is their

land administration, in support of their own development.

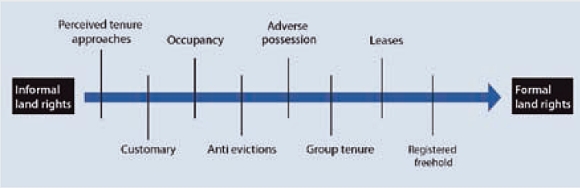

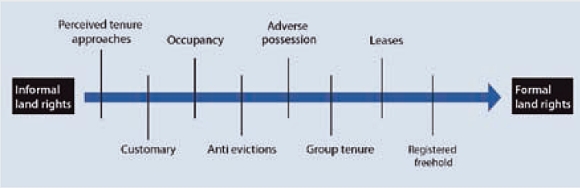

UN-HABITAT proposed the ‘continuum of land rights approach’ in 2003 and this

was further developed and adopted by the Global Land Tool Network partners. An

example of the continuum is given in Figure 3.

The continuum of tenure types is a range of possible forms of tenure

which can be considered as a continuum. Each continuum provides

different sets of rights and degrees of security and responsibility.

Each enables different degrees of enforcement. Across a continuum,

different tenure systems may operate, and plots or dwellings within a

settlement may change in status, for instance if informal settlers are

granted titles or leases. Informal and customary tenure systems may

retain a sense of legitimacy after being replaced officially by

statutory systems, particularly where new systems and laws prove slow to

respond to increased or changing needs. Under these circumstances, and

where official mechanisms deny the poor legal access to land, people

tend to opt for informal and/or customary arrangements to access land in

areas that would otherwise be unaffordable or not available

(UN-HABITAT:2008). |

Figure 3: GLTNs Continuum of Land Rights.

In conclusion there is an urgent need to have a land information system that

works differently and in addition to the conventional land information system.

Land tenure types, which are not based on formal cadastral parcels and which are

not registered, require new forms of land administration systems.

3. The STDM Tool: Closing the Gap

The concept of STDM is closing the gap, a standard for flexible ‘people

– land’ relationships.

The Social Tenure Domain Model (STDM) is basically about people. It is about

all people and all types of ‘people – land’ relationships. How can informal

settlements be “illegal settlings”? People depend on land for living. Every

human being needs a place – a safe place.

The STDM is an initiative of UN-HABITAT to support pro-poor land

administration. STDM is meant specifically for developing countries, countries

with very little cadastral coverage in urban areas with slums, or in rural

customary areas. It is also meant for post conflict areas. The focus of STDM is

on all relationships between people and land, independently from the level of

formalization, or legality of those relationships.

The STDM is under development as an ISO-standard as a so called

“specialisation” of the Land Administration Domain Model (LADM). The word

“specialisation” means that there are some differences in terminology: what a

“real estate right” is in a formal system is considered as a “social tenure

relationship” in STDM. Note that a formal right is also a social tenure

relationship, but not all social tenure relationships are formal land rights.

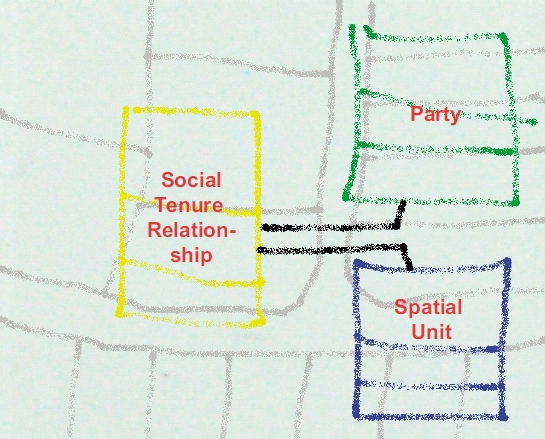

‘People – land’ relationships can be expressed in terms of persons (or

parties) having social tenure relationships to spatial units.

Parties are persons, or groups of persons, or non natural persons,

that compose an identifiable single entity. A non natural person may be a tribe,

a family, a village, a company, a municipality, the state, a farmers´

cooperation, or a church community. This list may be extended, and it can be

adapted to local situations, based on community needs.

Land rights may be formal ownership, apartment right, usufruct, free

hold, lease hold, or state land. It can also be social tenure relationships like

occupation, tenancy, nonformal and informal rights, customary rights (which can

be of many different types with specific names), indigenous rights, and

possession. There may be overlapping claims, disagreement and conflict

situations. There may be uncontrolled privatisation. Again, this is an

extensible list to be filled in with local tenancies. A restriction is a

formal or informal entitlement to refrain from doing something; e.g. it is not

allowed to have ownership in indigenous areas. Or it may be a servitude or

mortgage as a restriction to the ownership right. There may be a temporal

dimension, e.g. in case of nomadic behaviour when pastoralist cross the land

depending on the season. This temporal dimension has sometimes a fuzzy nature,

e.g. ”just after the end of the rainy season”.

Spatial units are the areas of land (or water) where the rights and

social tenure relationships apply. According to the LADM/STDM ISO-standard those

areas can be represented as a text (“from this tree to that river”), as a single

point, as a set of unstructured lines, as a surface, or even as a 3D volume.

This range of spatial unit representation can cover community based land

administration systems, or rural, or urban, or other types of land

administrations, like marine cadastres and 3D cadastres. Surveys may concern the

identification of spatial units on a photograph, an image or a topographic map.

There may be sketch maps drawn up locally. A sketch map may be drawn on a wall

where a photograph is taken from.

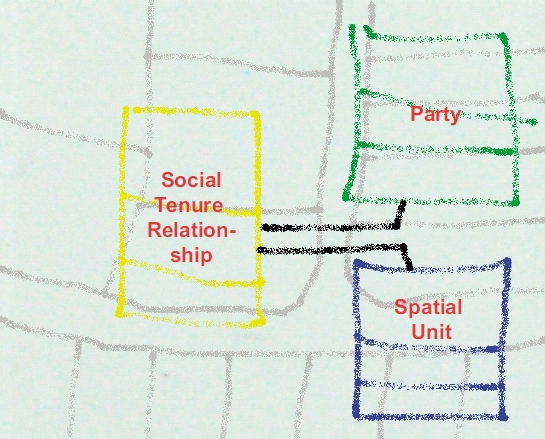

See Figure 4 for the core – parties, social tenure relationships and spatial

units – of the STDM.

Figure 4: The core of the STDM: parties (tribes, people, villages,

co-operations, organisations, governments), social tenure relations (‘people –

land’ relationships, which can be formal, informal, customary or even conflict),

and spatial units (representations from reality where the social tenure occurs,

can be represented as sketch based, point based, line based, polygon based).

In conclusion, the flexibility of STDM is in the recognition that parties,

spatial units and social tenure relationships may appear in many ways, depending

on local tradition, culture, religion and behaviour. Recordation in STDM may not

only be based on formal registration of formal land rights, but may also be

based on observations in reality, resulting in recordation of informal land use

rights. This is also one of the principles of FIG’s ‘Cadastre 2014’.

4. The Benefit of STDM: Support in Sustainable

Development

The provision of land information in all areas and for all citizens

will support in poverty eradication.

Hernando de Soto states that “civilised living in market economies is not

simply due to greater prosperity but to the order that formalised property

rights bring”. If the world’s community is sincerely of the opinion that

appropriate land administration systems are required for the eradication of

poverty, sustainable development and economic development, then it will be

evident that attention should be devoted primarily to the land administration

systems of developing countries.

Until today most countries (or states, or provinces) have developed their own

LAS. Some countries operate a deeds registration, while others operate a title

registration. Some systems are centralized, and others decentralized. Some

systems are based on a general boundaries approach, others on fixed boundaries.

Some LAS have a fiscal background, others a legal one.

STDM can contribute to sustainable development by the provision of a

flexible, unconventional land administration. This can be seen as an extension

to existing LAS. This may have a start in community based mapping processes,

supporting the mapping of land and property rights. Often local communities lack

knowledge on land laws and areas where those communities are living are not

administered. Many organisations have attention to this issue and there are

networks like the ‘indigenous mapping network’, established by anthropologists.

Also slum mapping in relation to tenure is an issue of international attention.

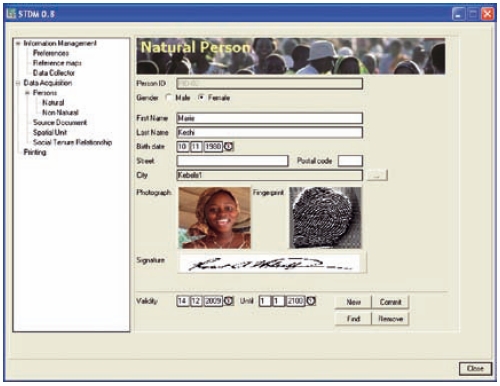

Depending on the local situation, different registrations or recordings of

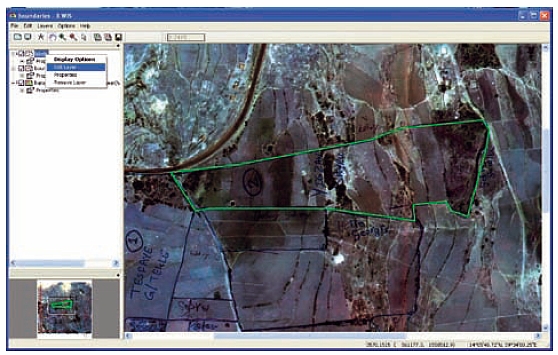

land rights are possible. In rural areas there can be spatial units covering

customary areas. Those spatial units can be recorded as ‘text based’ spatial

units, where boundaries are described in words. Or as ‘line based’ spatial

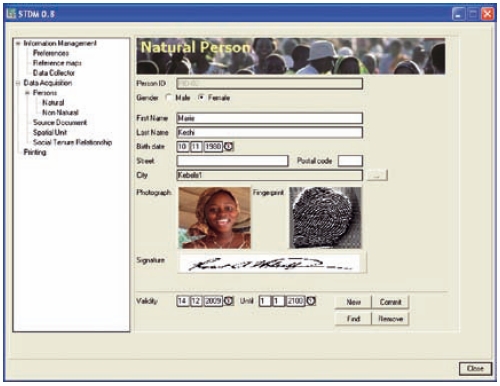

units, drawn on low accurate satellite images; see Figure 5. The tribe may be

represented by its chief. Formal property based spatial units can concern

formally registered ownership with related owner and with identified boundaries

by accurate field surveys. Persons living in ‘structures’ in slum areas may be

identified by fingerprints; see Figure 6. The social tenure relationship to the

spatial units may be represented by points collected with hand-held GPS

instruments – source documents may be printed from websites providing spatial

data. Spatial units in urban business districts can be conventional parcels with

high accurate boundaries. Spatial units in residential areas can be derived from

aerial photographs. If all data are collected in the same structure (Party –

Social Tenure Relationship – Spatial Unit) then the integration with a formal

LAS is possible.

The STDM approach will open up new markets to the land industry and it will

also be an opportunity to develop new skills and to improve management skills.

STDM can make it possible for all citizens to be covered by some form of LAS,

including the poor, thereby improving the land management capacity of the land

industry, as well as addressing upcoming challenges such as climate change.

Also, STDM can contribute to poverty reduction, as the land rights and claims of

the poor are brought into the formal system over time. It will improve their

security of tenure, increase conflict resolution, limit forced evictions, and

help the poor to engage with the land industry in undertaking land management

such as city wide slum upgrading or rural land management.

Figure 5: Collected data on top of a satellite image, drawn with pen.

Paper with sufficient quality is needed for use in the field: dust, sunshine and

water… and: many hands holding the paper.

Figure 6. Screendump STDM prototype software. An example where a

fingerprint and a photo of a land user are represented in the user interface.

This person can be related to spatial units (e.g. a single point) via social

tenure relations.

5. The Use: Simple Approach, Unconventional

Transactions

Mindset – this is an invitation not to start saying why the STDM

implementation is impossible because of existing legislation or because of

existing institutional settings. No, it is an invitation to start thinking how

STDM could be implemented to represent all ‘people – land’ relationships, which

can be observed in a community. Starting as a community based land information

system, that can be linked with, and eventually incorporated into a formal

system in the future.

The fact has to be accepted, that more social tenure relationships exist than

statutory land rights, especially at the political and higher administrative

levels. This is best expressed by inclusion in a land policy. The relevant land

agencies and involved private practitioners need to be willing to adapt their

ways of working to allow for dealing with the concepts of STDM as compared to

the ‘conventional land administration’ approach, including recognition of a

range of rights and mechanisms to gather the date of these rights on a community

based participatory approach.

Expertise is needed both in land administration and in ICT for each office

where the STDM software is used. The dilemma between community access and the

scale needed for ICT support needs to be solved in an appropriate manner.

Awareness and a culture of updating that means (a) for the social tenure holders

the awareness that they should report changes in their social tenure

relationships and (b) for the administrative system supporting STDM, that they

should process reported changes and (c) keep the requirements for reporting

simple enough to remain accessible for all, including the poor.

First the data need to be acquired. Communities (villages, co-operations,

slum dwellers organisations, or non governmental organisations) can organise

this. However, they are in need of tools.

On-site tests have been performed of the potential use of high resolution

satellite images to establish parcel index maps in selected villages. After

printing the images on paper in a 1:2000 scale, the boundaries of spatial units

were determined in the field using a pencil. The data collection in the field

was performed in the presence of land right holders and local officials. Apart

from the boundaries, administrative data like village names were collected. The

understanding of the paper prints in a 1:2000 scale was high, which makes the

process very participatory.

After field data acquisition the images, with drawn boundaries on it, were

scanned and brought back on top of the original image. The drawn boundaries were

vectorised and got identifiers. During field data collection preliminary

identifiers may be used. After vectorising the spatial data can be linked to the

person data using a spatial tenure relationship. Then the data have to be

brought to the local communities for public inspection, e.g. by the projection

of images and boundaries on a screen (if electricity is available). Local people

can be invited to check the data.

Later on it should be possible to perform unconventional transactions; e.g.

to change a social tenure relationship from “informal” to, for example,

“occupation” and later to “free hold”.

Hand-held GPS based data capture is possible, however not understood by the

local people. In general it can be stated that imagery or tape based

observations are well understood with regard to participatory approaches. In

STDM evidence from the field can be scanned and included as an authentic source

document. See Figure 7. Different types of source documents are possible:

images, maps, photo’s, etc.

Figure 7: Screendump STDM prototype software. An example case where drawn

boundaries are vectorised to closed polygons. Those polygons can be related to

persons via social tenure relationships.

Capacity building is needed before going to the field. This is easy with

images. The use of ‘digital pens’ seems very interesting for data collection

purposes. With digital pens, the drawn lines on the paper images can be read by

a computer and are geo-referenced immediately. This means that scanning is not

needed.

The use of STDM is most relevant with regard to the maintenance of the data.

How to go from an informal social tenure relationship to a formal one and from a

personal right of use to a formal one? The inventory of informal rights could be

seen as a “what to do list” after integrating the land data collected by the

local community with data from a Land Administration Authority – maybe in

co-operation with other institutions. Sometimes there are objections in

recognising informal rights; the “informal rights” are

called “illegal rights”. This is in fact neglecting what can be observed in

reality. The officials know this. People need a shelter somewhere and in many

cases the government did observe informal areas but did not interfere for a long

time.

How to move from a conflict situation (conflicting claims) to a formal one?

Again a “what to do list” for the government – upgrade the rights or take other

decisions based on the recordation of rights.

Women’s access to land – this can be organised by registration of shares in

rights. This is supported in STDM.

Data quality of spatial data may be improved in a later stage of development.

Note that there may be a serious need for accurate geo data in slum areas: the

value of land in slum areas near city centres can be very high.

In conclusion, the STDM concept is supportive in community based data

acquisitions. This gives people the feeling that the data are their own data.

Later the data can be formalised and integrated in formal systems. This is

possible because of a standardised approach.

Figure 8: Land rights of people living in slum areas are mostly not

recognised or often the situation is considered to be illegal. In any case

inclusion in formal land administrations is not possible. Extensions to formal

land administrations are urgently needed allowing recordation of all people to

land relationships. © Christiaan Lemmen

6. The Process: Developing the STDM

The status and the way forward to completion.

The Global Land Tool Network (GLTN), a coalition of international partners,

including FIG and ITC, has taken up this challenge and is supporting the

development of propoor land management tools, to address the technical gaps

associated with unregistered land, the upgrading of slums and rural land

management, among other things.The security of tenure of people in these areas

relies on forms of tenure different from individual freehold. Most off register

rights and claims are based on social tenures. GLTN partners support a continuum

of land rights, which includes rights that are documented, undocumented, from

individuals and groups, from pastoralist, in slums, which are legal, illegal and

informal.

The technical gap covered by STDM is on the critical path of the delivery of

a number of Millennium Development Goals namely, Goal 1 on food security, Goal 3

on the promotion of gender equality and the empowerment of women, and Goal 7 on

ensuring environmental sustainability, including improving the lives of slum

dwellers.

A first prototype of STDM1 has been developed at ITC for the purpose to test

the concept, the look and feel, and the way transactions are implemented. As

soon as this is evaluated a version will be available to support the input and

maintenance of comprehensive data sets.

The specifications have to be available for software development by open

source communities or by commercial software suppliers. Open Source means that

developments in software can be shared. Both Open Source software and commercial

software will be needed – depending on the level of development of land

administration. Relative small amounts of data may be manageable with open

source software. Huge amounts of data, to be accessible 7 × 24 hours, will

require information management by commercial software, at least as long as there

is insufficient expertise on Open Source products (database and GIS).

In conclusion, STDM is a pro-poor tool and the development of the concept and

a first prototype is funded by GLTN and supported by FIG – the global community

of land administration professionals. The role of FIG is therefore in the area

of advocating this model from a professional point of view and to provide the

professional environment for its development and implementation.

Augustinus, Clarissa (2010): Social tenure domain model: what it can mean

for the land industry and for the poor. XXIV FIG International Congress:

facing the challenges, building the capacity, April 2010, Sydney, Australia.

Augustinus, Clarissa, Christiaan Lemmen and Peter van Oosterom (2006):

Social tenure domain model: requirements from the perspective of pro-poor land

management. 5th FIG regional conference: promoting land administration and

good governance, March 2006, Accra, Ghana.

De Soto, Hernando (2003): The mystery of capital: why capitalism triumphs

in the west and fails everywhere else. New York, NY, US. Basic Books.

Lemmen, Christiaan, Clarissa Augustinus, Peter van Oosterom, and Paul van der

Molen (2007): The social tenure domain model: design of a first draft model.

FIG Working Week 2007: strategic integration of surveying services, May

2007, Hong Kong SAR, China.

UN (2000): United Nations Millennium Goals Declaration. United Nations

General Assembly, New York, US.

Williamson, Enemark, Wallace, and Rajabifard (2010): Land Administration

for Sustainable Development. ESRI Press Academic. Redlands, California, US.

Zevenbergen, Jaap and Solomon Haile (2010): Institutional aspects of

implementing inclusive land information systems like STDM. XXIV FIG

International Congress: facing the challenges, building the capacity, April

2010, Sydney, Australia.

Copyright © International Federation of Surveyors, Global

Land Tool Network and United Nations Human Settlements Programme (UN-HABITAT),

March 2010

All rights reserved

International Federation of Surveyors (FIG)

Kalvebod Brygge 31–33

DK-1780 Copenhagen V

DENMARK

Tel. + 45 38 86 10 81

E-mail: FIG@FIG.net

www.fig.net

Published in English

Copenhagen, Denmark

ISBN 978-87-90907-83-9

Published by

International Federation of Surveyors (FIG)

Front cover: Ethiopia (left), Ghana (middle) © Christiaan

Lemmen;

Bolivia (right) © Ximena Pereira

DISCLAIMER

The designations employed and the presentation of material in this publication

do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the

secretariat of the United Nations concerning the legal status of any county,

territory, city or area or its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of

its frontiers or boundaries regarding its economic system or degree of

development. Excerpts may be reproduced without authorization, on condition that

the source is indicated. Views expressed in this publication do not necessarily

reflect those of the United Nations Human Settlements Programme, the United

Nations and its member states.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Without the support and contribution of Dr. Clarissa Augustinus, Prof. Dr. Peter

van Oosterom, Dr. Solomon Haile, Prof. Paul van der Molen, Prof. Dr. Jaap

Zevenbergen and Prof. Stig Enemark the concept of the Social Tenure Domain Model

could not have been developed. Also the ISO 19152 Project Team, drafting the

Land Administration Domain Model, were constructive in their support for the

Social Tenure Domain Model. This is a big step forward in the development of

Land Administration Systems. Martin Schouwenburg, Liliana Alvarez, Jan van

Bennekom-Minnema and Monica Lengoiboni prepared the first STDM prototype

software. Remy Sietchiping and Hemayet Hossain provided valuable advice during

the development. Thanks for all your support.

Editors: Harry Uitermark and Christiaan Lemmen

Design: International Federation of Surveyors, FIG

Printer: Oriveden Kirjapaino, Finland

|