Article of the Month -

October 2006

|

Gender Dimensions of Land

Customary Inheritance underCustomary Tenure in Zambia

Ms. Nsame Nsemiwe, Zambia

This article in .pdf-format

This article in .pdf-format

1) This paper is based on the paper written and presented by Ms. Nsame

Nsemiwe at the XXIII FIG Congress in Munich, Germany, 8-13 October 2006.

The FIG Council has decided to award the Congress Prize to two papers

presented by Ms. Nsemiwe. The other paper is

"Negotiating the Interface: Struggles Involved in the Upgrading of

Informal Settlements -a Case Study of Nkandabwe in Kitwe, Zambia".

Keywords: Customary inheritance, customary tenure, access to land,

security of tenure, land distribution, land management, land administration,

women, poverty reduction

SUMMARY

Land is the focal point of economic growth and the most valuable asset on

earth as it is the source of all human survival. It is a resource that must

be properly managed in order to ensure that everyone in a particular society

benefits from its use and that uses of land are not environmentally damaging

and where possible contribute to the sustainable development and poverty

reduction in an economy. While we may have diverse problems related to land

all over the world especially in developing countries, secure tenure, access

to and ownership of land should be identified as a right of every human

being. Women are at the focal point of rural agriculture, development and

poverty reduction but the majority of them face serious constraints in

access to and control over land. Normally the right to access, ownership and

control over land are determined by patriarchal marriages and inheritance

systems that are prevalent in many developing nations which favour males

unlike their female counterparts in terms of the rights to control and

disposal.

In most countries land under customary tenure accounts for most of the

rural areas and according to the World Bank 2005 annual report, seventy

percent of the world's poor live in rural areas. The rural poor produce food

on land, build houses and depend on land for their social status and power.

Therefore, sustainable rural development must include agricultural

development which is truly enhanced by good land administration and

management. In the quest to promote rural development it is essential to

ensure that women have equal access rights to land knowing that women

account for half of the world's total population but only own 1% of the

world's wealth Rural women alone are responsible for half of the world’s

food production and between 60 and 80 percent of food production in most

developing countries. They are also the major implementers of most

developmental decisions and are a catalyst for sustainable development and

poverty reduction. To reduce hunger and poverty and promote sustainable

development, efforts must be made to address these inequalities

The role of a surveyor is thus very important in ensuring that people all

over the world have an opportunity to access or own land so as to contribute

to development and reduce poverty as their profession is closely tied to

land. The expertise of surveyors in planning, recording, distributing,

management and advice in decision making on land related issues is vital in

many economies especially those of developing countries. Surveyors can make

a difference in ensuring that every person in the world has access to and

can own land, and by so doing they will definitely contribute to the changes

going on in the world positively. The paper discusses customary inheritance

practices and their impact on distribution of land, access to land, security

of tenure and poverty reduction in areas under customary tenure or rural

areas.

1. INTRODUCTION

The task of managing land use and the earth’s resources is gaining

increasing importance due to the rising world population and economic

growth. Land is the basic resource for human survival and development and

all human activities such as mining, agriculture, tourism, building take

place on land. It also performs basic and fundamental functions that support

human and other terrastrial systems such as to produce food, fibre, fuel,

water or other biotic materials for human use: provides biological habitats

for plants, animals and micro-organisims: regulates the storage and flow of

surface and ground water; provides physical space for settlements, industry,

recreation and enable movement of animals, plants and people from one area

to another. One of the greatest writers on land – Henry George, who may also

be referred to as the foremost land economist, appreciated the value of land

and once remarked that "...land is the habitation of man, the store-house

upon which he must draw for all his needs, the material to which his labor

must be applied for the supply of all his desires; for even the products of

the sea cannot be taken, the light of the sun enjoyed, or any of the forces

of nature utilized, without the use of land or its products. On the land we

are born, from it we live, to it we return again- children of the soil as

truly as is the blade of grass or the flower of the field. Take away from

man all that belongs to land, and he is but a disembodied spirit" (George,

1879, rpt. 1958).

Mans life depends on land, thus any fight against poverty must give

highest priority to land issues such as its access, distribution,

management, administration, ownership and tenure security, especially in

developing countries.Due to various traditions, customs and culture

especially in Africa, it is a reality that there is inequality between men

and women in the control over, access to, ownership and management of land.

This is more prevalent in areas under customary tenure some of which may

also be referred to as rural areas where women may have less access to land

and tenure is not also very secure as compared to men and one of the factors

contributing to this is the inheritance practices that are present in some

of these areas.

2. RELEVANCE OF STUDY

The issue of customary inheritance practices related to land under

customary or traditional tenure disadvantaging womens access to land and

secure tenure has been hotly debated all over the world, but it still exists

and is very real, especially in Africa. Knowing that most areas that are

under customary tenure are mostly rural areas which in most cases lag behind

in development compared to urban areas it is important to find ways to

accelerate economic growth. The World Bank (2005a) reveals that both

experience and reserch show that for this acceleration to take place women

and men need to be helped to become equal partners in development, with an

equal voice and equal access to resouces. It indeed is right to say that

when we ensure equal land rights for men and women economic opportunities

will increase, investment wil be encouraged in land and food production as

well as improved family security during economic and social transition and

this will lead to better land stewardship (FAO, undated). Steinzor (2003)

argues that women’s lack of property and inheritance rights has been

increasingly linked to development-related problems faced by countries

across the globe, including low levels of education, hunger, and poor

health, therefore it is essential to continue discussing these issues until

marginal progress is achieved. In addition, the subject of women’s access to

land, has been discussed under Commission 7 of the International Federation

of Surveyors (FIG), within the general context of land administration. This

shows that there is still a need to address this issue and surveyors in

today’s world have got an important role to play to ensure that some of the

challenges related to land administration and management such as unfair

distribution of land, womens lack of access to land and lack of security of

tenure under customary tenure are overcome.

3. FEMINIZATION OF POVERTY

Poverty is the negative analogue of human development. It may manifest

itself in various ways which may include the lack of basic needs such as

food which causes hunger, proper health services and education system,

shelter or lack of adequate infrastructures. Poverty affects men and women

in different ways and this has led to the widespread emergence of phenomenas

such as ’ferminization of poverty’. Muylwijk (1995) describes ‘feminization

of poverty’ as the process of women losing rights to fertile land, access to

labour and other production resources and of the expansion of women’s

responsibilities in comparison to those of men.

The issue of globalization and the spread of the money economy to the

remotest communities such as rural areas, makes women more disadvantaged

because land becomes capital. Researchers such as Lee- Smith and Trujillo

(1999) have argued that women's lack of equal property rights with men is a

major cause of the feminization of poverty. This is definitely true and as

we try to reduce poverty it is essential that grass root causes of poverty

such as womens lack of access to land are addressed. The World Bank

President Mr . James D. Wolfensohn observed that where gender inequality

persists, efforts to reduce poverty are undermined and that numerous studies

and on-the-ground experiences have shown that promoting equality between men

and women helps economies grow faster, accelerates poverty reduction and

enhances the dignity and well being of men, women and children (The World

Bank, 2005b).

When we are fighting to reduce poverty we must ensure that it is coupled

with sustainable development, so as to make the efforts continue for a long

time. The 1987 Brundtland Report defined sustainable development as

development which meets the needs of the present without compromising the

ability of future generations to meet their own needs. Sustainable

development therefore entails using resources to the maximum and this calls

for effectiveness in delivering desired resources. The final edition of the

Report on the Bathurst declaration also makes this very clear by stating in

its executive summary that without effective access to property, economies

are unable to progress and the goal of sustainable development cannot be

realised and it lists womens access to land as one of the overall, most

serious problems facing the relationship between land and people. Therefore,

for sustainable development to take place land must be properly distributed,

managed and secure user rights must be present for everyone in a particular

society.

4. PROMOTING EFFECTIVE LAND MANAGEMENT BY WOMEN

Land as a resource covers a wide ecological dimension and is a source of

wealth for every economy and it is a tool for poverty reduction. Land is

generally abundant in supply but desirable land which can be used for

cultivation and other income generating ventures is scarce. The heavy

reliance on land for development makes sound management of this important

resource so as not to compromise the needs of future generations. Suon and

Onkalo (2004) define land management as a system of planning and management

methods and techniques that aim at integrating ecological with social,

economic and legal principles in the management of rural and urban [land]

development purposes to meet changing human needs, while simultaneously

ensuring long-term productive potential of natural resources and the

maintenance of the environment and cultural functions. Land management aims

at sustainable use of land as a resource. Sustainability in this term

implies that land management should promote sustainable development by

preserving the primary environmental resources such as air, soils and water

for present and future users.

Kariuki (2006) asserts that for women to be effective managers of land,

three issues under land need to be addressed. These include land use, land

rights and land administration. Land use involves skills and knowledge. Land

rights will consider the terms and conditions which individuals and

households hold, use and transact land (land tenure). Other issues include

land scarcity and conflicts over land. According to the Bathurst Declaration

on Land Administration for Sustainable Development issued in October 1999,

tenure may be defined as the way in which the rights, restrictions and

responsibilities that people have with respect to the land (and property)

are held. It is a set of rights a person or organization holds in land, is

one of the principal factors in determining the way in which resources are

managed and used, and the manner in which the benefits are distributed.

Security of tenure for women must be viewed as a key link in the chain from

household food production to national food security.

Land administration is the “process of determining, recording and

disseminating information about ownership, value and use of land when

implementing land management policies” (UN/ECE Land Administration

Guidelines). It considers the various institutions that deal with land at

the local or community level, civil societies and various government and

private sector bodies. It aims to manage land in a jurisdiction by providing

security of tenure, a suitable environment for the land market and for

public land management in general (Bathurst Declaration). The problems with

land and women range from tenure disputes, unsuitable land legislation, land

administration, land grabbing and invasions. These have led to unequal

distribution and insecure land tenure. For women these problems are

magnified because of inheritance laws, modern legislation and cultural

issues which in many cases bar a woman from owning land outright or without

the consent of her father or husband. The dichotomy between ‘who tills the

land’ and ‘who holds the user rights’ has thus been a critical issue in

sustaining rural land management, especially with the increase in the

female-headed households owing to the ravages of HIV/AIDS and urban

migration of men in search of employment in urban areas.

5. INHERITANCE AS A MEANS OF DISTRIBUTING LAND

In most areas under under customary tenure distribution or allocation of

land is mainly according to customary or traditional law, purchase or

inheritance. This paper will focus on the distribution of land through

inheritance. The Women and Law in Southern Africa (1994) define inheritance

as an institutional act of apportioning and receiving the property of a

deceased person. It is the practice of passing on property, titles, debt and

obligations upon the death of an individual and varies from one culture,

region, tribe or country. In most of these areas land has assumed the status

of a vital asset, necessitating the need for its protection against

alienation outside the clan or family, on the assumption that girls marry

away from their parental homesteads, they are not entitled to inherit land

exclusively, lest they transfer the land outside the clan or family through

marriage. The principle of protecting clan land applies to male and female

heirs. However, the principle is applied in a discriminatory manner because

while male heirs land rights remain intact during their absence, females

have no such advantage, especially in the case of widows.

Inheritance may be through the bilineal system which is inheritance

through either father or mother. Inheritance and succession determined

through the mother is known as matrilineal while inheritance and succession

which is determined through the male/ father’s lineage is referred to as

patrilineal or gavelkind which is the most common inheritance system in

Africa (Hilhorst, 2000:186). Some cultures also practice a system of

inheritance whereby all property goes to the eldest child (first born) or

son and this is known as primogeniture. According to Lee- Smith and Trujillo

(1999), work done on women's access and rights to land and housing by UNCHS

(Habitat)'s shows that women are disadvantaged in societies where male

inheritance customs are strong. Some societies have a system where

everything is left to the youngest child while other societies every child

is entitled to inherit an equal share. Hilhorst (2000) notes that

matrilineal systems have also transformed. She further argues that in

societies where polygamy is practiced, the share of family land received by

children on their father’s death will often depend on the status of their

mother within the marriage. In addition the number of children a wife has

will also contribute to the share she will inherit and widows with no

children are normally the most vulnerable as they may not even inherit any

property or land.

6. WOMEN’S ROLES IN SOCIETY AND THE IMPORTANCE OF EQUALITY IN THE

DISTRIBUTION OF LAND IN RURAL AREAS

In almost all societies, women play both reproductive and productive

roles. The latter comprise of work done by both women and men for payment in

cash or kind. Despite their important productive roles relating to land,

they also have responsibilities of child bearing, managing their homes,

looking after children, taking care of the sick and elderly, etc.

Furthermore in almost all rural communities agriculture is the main economic

activity providing employment for a large number of the population. Although

women contribute substantially to agriculture and many other activities they

continue to be largely marginalized and undervalued. The role of women in

relation to their environment can be further understood by Redclif (1991)

who was of the view that:

Women’s responsibility for reproduction as well as production places them

in a disadvantageous position in relation to the new market opportunities.

It is women who nature the children, feed the family and provides much of

‘casual’ paid labour, which underpins commodity production for the market.

It’s also women, actually, who interact most closely with the natural

environment: collecting the fuel wood, carrying the household’ s water long

distances, tendering the vegetable garden. Women therefore bear the brunt of

environmental degradation, through their proximity and dependence upon the

environment, while also being held responsible for this decline. Unable to

reverse the erosion of resources to which the household access, women are

placed in the impossible positions of acting as guardians of an environment

which is as undervalued and exploited as their own labour.

Due to relationship with the products of uncultivated land in traditional

management systems, women have lost access to these resources as land is

alienated for other uses in modern economies. Secure land rights foster

sustainable land management and are believed to have a positive impact on

the reduction of poverty, as women will firstly, try and find ways in which

to preserve and regenerate their land thus providing sustainable farming

practices. In other words with secure tenure women can invest in land rather

than destroy the land’s productive potential. Secondly, women can plan

quickly to adjust resource allocation decisions under changing climatic or

economic conditions. Thirdly, women can rely on the productive results of

their labour. Lastly, women will be empowered in decision making since they

can decide what crops to grow, what techniques to use, what to consume and

what to sell. The lack of access to land and an insecure tenure leaves women

with no productive or non productive resources that may be required as means

of survival and this will definitely weaken the socio-economic status of

women. Zambia’s Poverty Reduction Paper (2004) notes that there are benefits

resulting from women’s access to land in terms of family and food security.

Food security in this context is the access by all people, at all times, to

enough food for an active and healthy life, therefore ensuring poverty

reduction.

7. THE IMPACT OF HIV/ AIDS

The HIV/AIDS epidemic is a major challenge facing many countries in

sub-Saharan Africa where according to a UNAIDS Report on the Global AIDS

Epidemic (2004) 75 percent of people of ages 15 to 24 with HIV/AIDS are

female.Within these countries, AIDS is becoming a greater threat in rural

areas than in cities. The Zambian poverty reduction paper (2004) states that

“since the first diagnosed case in Zambia in 1984, HIV/ AIDS has become

increasingly widespread with an estimated adult prevalence of 14 per cent in

rural areas and 28 per cent in urban areas in the 15 – 49 year old age

group.” The report further notes that although the epidemic is showing signs

of stabilization in urban areas, the rates continue to rise in some rural

areas. Studies by Women and Law in Southern Africa confirm that the

situation of women in Zambia poses serious difficulties and challenges

especially when the gender dimension and the socially constructed roles of

men and women are considered. While both men and women are affected by

HIV/AIDS, it is important to recognize that this occurs in different ways

for men and women, because men and women play different roles, have

different needs and face different constraints in responding to the

epidemic. Due to high death rates caused by the HIV/AIDS related illnesses,

many women are being left without land or property which is an essential

resource for their livelihoods especially due to the customary inheritance

practices in most rural areas. In the past widows were regarded

sympathetically and were allowed to remain in their husbands villages even

when they were not inherited but due the change of societal values, economic

hardships and devastating effects of HIV/AIDS family ties have loosened. the

right to occupy and use land was previously passed on to children of the

deceased especially when the widow was kept within the family of her

deceased husband through widow inheritance. Men are reluctant to inherit

widows and widows are reluctant to be inherited as the late husbands family

fear being infected with the disease after inheriting the widow and also

fear the process of taking care of her in the case that she also gets sick.

This leads to widows being dispossessed of land by being forced to leave

their husbands villages because the rightful person to inherit the

deceased’s use and occupation of land is the nephew of the deceased person

(Macmillan, 2002). Women also experience stigmatization and mistreatment and

in some cases there is a stigma that encourages the view that those who are

HIV positive will not be able to properly use the land and therefore they do

not need it. The sale of land by land holders at distress prices in order to

look after those who are sick is also common.

Kariuki (2006) suggests that there is growing evidence to suggest that

where women’s property and inheritance rights are upheld, women acting as

heads and/or primary caregivers of HIV/AIDS-affected households are better

able to mitigate the negative economic and social consequences of AIDS. She

further asserts that the denial of property and inheritance rights

drastically reduces the capacity for households to mitigate the consequences

should a member be infected with HIV. Access to resources such as land by

women will enable women fight the socio economic impacts of HIV/AIDS and

Kangwa (2005) seems to suggest a similar notion when he argues that because

poverty and HIV/ AIDS have the greatest impact on women, all initiatives

must priotise the importance of women’s rights to fair and equal treatment,

as well as their specific needs and challenges.

8. THE ZAMBIAN CASE

Zambia is a subtropical country located in the middle of Southern Africa

and is administratively divided into nine provinces which, in turn, are

divided into seventy-two districts. There are basically two types of tenure

present in this nation, namely customary and state. Customary land is that

held on the basis of tribe, residence or community of interest. Customary

tenure which is mostly in rural areas is legally recognized and accounts for

more than 90 per cent of the land in Zambia. The remaining small portion of

land is state land which consists mainly of land in urban areas and is not

in the jurisdiction of traditional leaders. According to the Land Act of

1995 part 1 Sec 3.1 all land is vested in the president. The traditional

leaders such as chiefs and headmen just act as custodians of the land

although there is no doubt they have a regulatory role over the acquisition

of land.

According to the Republic of Zambia, 2004: Poverty Reduction Strategy

Paper poverty is most prevalent in the rural areas where most livelihoods

are agriculture-based. The paper further asserts that Zambia is abundantly

endowed with resources that are required to stimulate agricultural and rural

development, in general, and poverty reduction in particular. Table 1 shows

the reality of poverty in rural and urban areas in Zambia between 1991-1998.

Table 1: The Evolution of Poverty in Zambia 1990-1996.

Source: CSO: Living Conditions in Zambia 1998

8.1 Access to Land under Customary Tenure or in Rural Areas

Women constitute 65 per cent of the rural labour force working on this

land contributing approximately 60 per cent of the total rural products. It

is, however, sad to know that women’s access to, control over and management

of land that sustains their livelihood is out of their hands. The Zambia

Land Alliance (2005) note that during their consultation process with

various communities in the country, they observed that women did not have

access to land as much as the men despite traditional land being free and

that the tendency to dispossess and remove widows and orphans from family

land upon the death of a husband/father, was widespread. It is evident that

inheritance problems are very evident today not just in the past.

There are seventy-three ethnic groups in Zambia and according to WLSA

(1994) these may be categorized into four social systems which include the

matrilineal ethnic groups which practice matrilocal residence (uxorilocal

marriages), such as the Bemba of Northern province and the Nsenga of Eastern

province; the matrilineal ethnic groups which practice patrilocal residence

(virilocal marriages), such as the Tonga of Southern Province and the Lunda

of North-Western Province; the patrilineal and Patrilocal ehnic groups, such

the Mambwe and Namwanga of Northern Province and the Ngoni of Eastern

Province; bilateral ethnic groups, such as the Lozi of Western Province.

These social systems are more prevalent in rural or under customary tenure

and their customs, cultures and even marriages play an important role in

access to land. The most prominent types of marriages are statutory and

customary marriages. Other types that are recognized are religious

marriages, namely Christian, Moslem and Hindu marriages. A Statutory

marriage is a marriage under the Marriage Act of the Laws of Zambia and may

also be referred to as a Civil or Ordinance Marriage

A customary marriage is a marriage that is conducted according to the

relevant Zambian customary law of the two parties. In the Zambian context,

such a marriage is usually viewed as a union between two families. There are

a number of requirements and procedures to be followed in the traditional

marriage. Firstly a number of transactions take place. These begin with the

approaching of the girl's family with a token symbol or payment called

Nsalamu (Bemba) or vulamulomo (Chewa - literally 'opening the mouth'). The

negotiations go back and forth depending on the traditions and customs of

the parties and culminate in the concluding of the marriage negotiations. A

customary marriage can be registered by the local court and by the rural

councils. A customary marriage is potentially polygamous, that is, during

such a marriage, there is no legal impediment to a man taking another woman

as his wife. Polygamous marriages are very common in Zambia and under

customary tenure it is normally unheard of for a married woman to acquire

land for herself. In cases where a man has more than one wife he apportions

a field to each wife and her children to plant, weed and harvest. The

problem mostly comes in when the husband dies as land and property are

allocated according to status of their mother within the marriage.

Polygamous marriages therefore, contribute a lot to inequality especially in

terms of rights to property and inheritance.

Customary marriages may also be virilocal or uxorilocal. Virilocal

marriages occur when a wife moves to her husbands homestead or village after

marriage, while uxorilocal occur when the husband or man moves to his wife’s

homestead or village after marriage. This also has an influence on

inheritance of land or property in a particular ethnic group incase of the

death of either the husband or wife. The many forms that marriage can take,

the basis (or lack) of marriage contracts, the practice of wife inheritance,

the growing prevalence of cohabitation, norms dictating dowry, and the

ongoing practice of polygamy strongly influence both customary and legal

partnerships and outcomes related to property and inheritance (Steinzor,

2003).

In a newspaper article dated 10th May, 2006 Mushota stated that

traditionally, it was believed that empowering a woman would lead to

marriages breaking and that land is wealth and once women have access to

land they will become self-reliant and won’t have to go through hard

marriage just because of dependency. In the same article Zijena said that,

“traditionally, most chiefs don’t give land to women without the husband’s

consent for fear of the woman becoming empowered and subsequently losing

respect for the husband,” She added that widows in most cases were now being

evicted from the land and that, in villages, women especially widows are

even required to vacate the land and leave it for the husband’s brothers

unless someone from the family marries her but since that custom is no more,

women are left with no land. Widows normally accept loss of property because

they are scared of being bewitched, some do not know their rights especially

towards property, while others find it is difficult to challenge in-laws.

Widows normally return to their natal villages where they start

cultivating land that belongs to their matrilineal male relatives. Women who

do remain in their husbands villages labour in their in-laws’ land where

they work on their mercy and may be chased at any moment. Some of the

customs related to access or ownership of land include widow inheritance

which is a practice where the widow becomes the wife of the successor of the

deceased. According to Machina (2004), thirty per cent of the rural

households are headed by women and are the poorest as they tend to have less

fertile, small plots of land than male-headed households. Most female headed

households are headed by widows and grandmothers characterized by the

ownership of the few productive assets and less access to land for

agricultural production. Short-term responses such as selling productive

assets and removing children from school worsen household poverty in the

long term and contribute to the feminization of poverty in Zambia.

A good example of an ethnic group that follows patrilocal systems of

inheritance is the Ngoni of Eastern Province. On a man’s death inheritance

is essentially on the principle of primogeniture (inheritance is by the

first born). This sort of inheritance has a special meaning to this ethnic

group as they have a social structure that is not only patrilineal but one

in which polygamy is common. According to Mvunga the context of

primogeniture amongst the Ngoni means the following: Firstly, it may mean

inheritance of a man’s estate by his eldest son, where all his children are

born of one and the same wife. Secondly, it may mean inheritance by the

eldest son of the senior house, where children are born of various wives in

a polygamous marriage. Lastly, it may mean inheritance by the eldest male

person who by virtue of belonging to a class of paternal relatives can be

described as the deceased’s nearest blood relative.

Due to the fact that polygamy is considered, inheritance follows what

Mvunga calls ‘principle of inheritance by house.’ House in this context

refers to the order of wives within a particular marriage. Thus seniority of

a house is determined by the sequence in time in which different wives get

married to the same husband. This means that the first wife will create the

senior house while the other wives will be of the junior house. It is the

eldest son of the senior home and not the eldest son of the father (assuming

there is such a one in other houses), who inherits the father’s estate. At

times a son from a junior house may be the heir to a father’s estate and

this only occurs if there is no son in the senior house, then an heir will

be sought in the next senior house which has a son. Though it is worth

noting that in very rear circumstances when the eldest son of a senior house

is failing, the next eldest daughter of the same house inherits the father’s

estates.

8.2 Relevant Legislation Affecting Women’s Access to Land in Zambia

Article 23 of the republican constitution allows for customary law and

practices to exist side by side with statutory law. Zambia’s dual legal

system means that people are governed by different and often contradictory

systems of law. General Law depends on English law, with many statutes new

and old being replicas of English rules of registration. Women’s access to,

control over and ownership of land are above all constrained by customary

law and by attitudes and practices, which reflect the subordinate position

under customary law, (Keller, 2000). Customary law is not codified but

comprises of unwritten social rules that are mainly passed on from one

generation to another. Customary law is based on the particular ideologies

operating on the premise that men are biologically superior to women and

varies from one ethnic group to another. This logic has also permeated all

instructions of socialization both tradition and constitution. Although a

lot of policies and laws have been put in place over the years concerning

equality in relation to land issues they receive a blind eye especially in

rural areas where the land is mostly under customary tenure. Ossko (2006)

asserts that in many countries besides written law, customary, informal laws

are parallel existing which are very important for a lot of people. He

further remarks that sustainable land administration has to take unwritten

laws into consideration if it wants to serve the entire society. This is

very true especially in most African countries.

The 2000 Land Policy states that ’while current laws do not discriminate

against women; women still lack security of tenure to land in comparison

with their male counterparts.’ The policy puts the blame on customary and

traditional practices. With this in mind the policy states that ‘thirty per

cent of the land, which is to be demarcated and allocated, is to be set

aside for women and other vulnerable groups.’ When a person dies without

leaving a will the 1989 Interstate Succession Act gives a provision for the

spouse to inherit twenty percent of the deceased estate. The problem is that

this law and many other laws that favour womens ownership of land are not

applicable in most areas that are under customary tenure especially the

remotest parts of the country where people have never even heard of such

laws.

Alot of international policies may apply in Zambia and just three of the

many will be discussed. The Convention on the Elimination of all forms of

Discrimination against Women (1979) which Zambia signed in 1980 and ratified

in 1985, discussed issues that directly affect the welfare of rural women

such as: adopting appropriate legislative and other measures, including

sanctions where appropriate, prohibiting all discrimination against women;

modifying or abolishing existing laws, regulations, customs and practices

which constitute discrimination against women, taking all appropriate

measures to eliminate discrimination against women in rural areas in order

to ensure, on a basis of equality of men and women that they participate in

and benefit from rural development. The United Nations Commission on Human

Rights Resolution 2002/49 affirms that “discrimination in law against women

with respect to having access to, acquiring, and securing land, property,

and housing, as well as financing of land, property, and housing,

constitutes a violation of women’s human right to protection against

discrimination.” The resolution also encourages “Governments to support the

transformation of customs and traditions that discriminate against women and

deny women security of tenure and equal ownership of, access to, and control

over land and equal rights to own property and to adequate housing.”

The "inheritance clause", which was birthed by the Super Coalition in

Beijing was aggresively debated and became a major item in the Platform For

Action. The Beijing conference also noted that environmental degradation

that affects all human lives often has a more direct impact on women, as

their health and their livelihood are threatened by pollution and toxic

wastes, large-scale deforestation, desertification, drought and depletion of

the soil and of coastal and marine resources, with a rising incidence of

environmentally related health problems and even death reported among women

and girls. The Platfoam also alluded to the fact that the most affected are

rural and indigenous women, whose livelihood and daily subsistence depends

directly on sustainable ecosystems. The documents mentioned and many others

that individual countries such as Zambia are affiliated to must be properly

analyzed to find ways in which they can be implemented so as to bring about

equality in the access to land between men and women under customary tenure

or in rural areas.

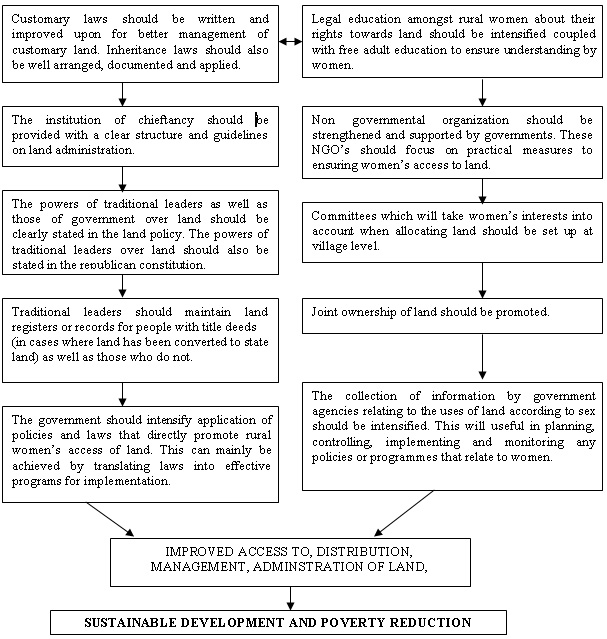

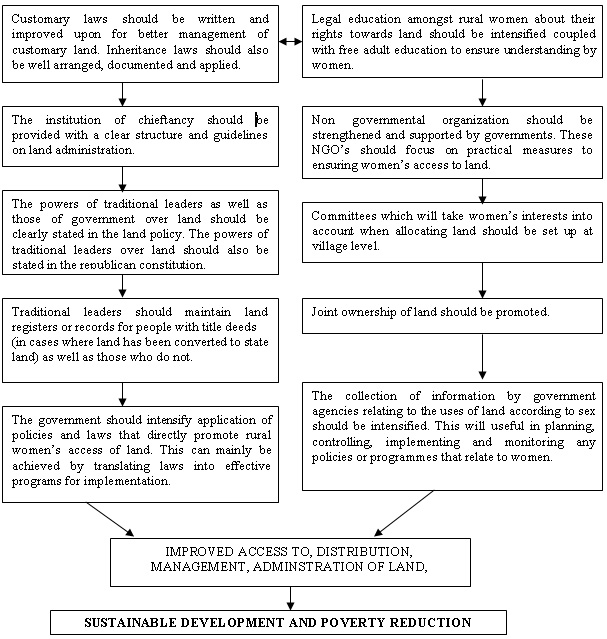

9. CONCLUSION AND RECOMMENDATION

The gap between who gets the land and who tills the land under customary

tenure is still very wide as men and not women make most decisions

concerning customary inheritance or allocation of land and it is very

difficult for women to own their own land. In view of the foregoing, the

following recommendations may be seen as a tool under customary tenure to

enhance women’s secure tenure and access to of land.

Land management in most areas under customary tenure or rural areas in

Africa is handicapped by customary practices such as inheritance that are

embedded in tradition, customs, family heads and lineage/clan leaders who

determine who gets the land. The improvement of the management of land under

customary tenure will surely have a direct effects on the access to,

distribution of land and promote secure user rights which will definitely be

an important step in ensuring food security and poverty reduction in nations

where women’s lack of access to land and security of tenure is prevalent. If

land management or land administration systems are improved and women have

better access to land through practical efforts, then surveyors will really

be seen to contribute positively to the change go in the world today.

Figure 1 Model for the improvement of land management under

customary tenure

REFERENCES

The Bathurst Declaration on Land Administration for Sustainable

Development, Report of the workshop on land tenure and cadastral

infrastructures for sustainable development, 18th - 22nd October 1999,

Bathurst Australia, Final Edition

Beijing Declaration and Platform for Action, Fourth World Conference on

Women, 15 September 1995,

http://www1.umn.edu/humanrts/instree/e5dplw.htm, accessed on 8-07-06

Brundtland Report- Our Common Future, 1987, avaialable on

http://www.ace.mmu.ac.uk/eae/Sustainability/Older/Brundtland_Report.html,

accessed on 22nd June, 2006

Food and Agriculture Organisation of the UN, Land Rights: A Gender

Perspective, available on

www.baobabconnections.org,

accessed on 27th May, 2006.

Lee-Smith D. and Trujillo C. 1999, The situation of women and land -

problems identified, CSD NGO Women's Caucus, Position Papers: Land

Resources, Land Management.

Government Republic of Zambia (1995), The Lands Act, 1995, Lusaka:

Government Printers.

Government Republic of Zambia (1989), The Interstate Act of 1995, Lusaka:

Government Printers.

Government Republic of Zambia (2000), The Land Policy, 2000, Lusaka:

Government Printers.

Henry. G,(1879) Reprint 1958. Progress and Poverty. New York: Robert

Schalkenbach Foundation, pp 295-296 also available on

http://www.cooperativeindividualism.org/carter-weld_on-henry-george-theories.html,

accessed on 26-05-06

Hilhorst T, (2000), Women’s Land Rights: Current Developments in

Sub-Saharan Africa. In Toulmic, C and Quan J (eds), Evolving Land Rights,

Policy and Tenure in Africa, London: Department for International

Development, International Institute For Environmental and Development and

Natural Resources Institute

Kangwa J, (2005), Land Tenure, Housing Rights and Gender-National and

Urban Framework: Zambia, UN-HABITAT

Kariuki C, ( 2006 ), The role of women in rural land management and the

impact of HIV/AIDS, Paper presented at the CASLE conference in Tanzania,

14th – 17th March 2006

Keller B, (2000), Women’s access to land in Zambia, Prepared for

International Federation of Surveyors (FIG), Commission 7( Cadastre and Land

Management).

Machina H, (2002), “Women’s Land Rights in Zambia: Policy Provisions,

Legal Framework and Constraints” Zambia Land Alliance, Presented at the

Regional Conference on Women’s Land Rights, held in Harare, Zimbabwe, from

26-30 May 2002.

MacMillan J, (2002), Women and Law in Southern Africa Research and

Educational Trust-Zambia, Presentation on HIV/AIDS and the Law: Challenges

for Women at FAO/SARPN from 24th-25th June 2002.

Muylwijk J, (1995), Gender Issues in Agricultural Research and Extension,

Autonomy and Intergration, In R.K Samanta (ed), Women In Agriculture:

Perspective, Issues and Experience, M D Publications PVT LTD, M D House, 11

Darya Ganj, New Delhi-110 002.

Mvunga P.M, (1x 7982), Land Law and Policy in Zambia, Maimbo Press, P.O

Box 779, Gweru, Zimbabwe.

Osskó A, (2006), Questions on Sustainable Land Administration, Promoting

Land Administration and Good Governance, 5th FIG Regional Conference, Accra,

Ghana, March 8-11, 2006

Redclift M, 1991, Sustainable Development: Exploring the contradictions,

Routledge II, New Fetterlane, pp 65 London EC4P 4EE.

Republic of Zambia (2000), The Poverty Reduction Strategy Paper

2002-2004, Lusaka, Zambia.

Steinzor N, (2003), Women’s Property and Inheritance Rights: Improving

Lives in a Changing Time, A project funded by the Office of Women in

Development, Bureau for Global Programs, Field Support and Research, U.S.

Agency for International Development with Development Alternatives, Inc

Suon S and Onkalo P (2004), Development of Curriculum for the Land

Management and Land Tenure Program in Cambodia, 3rd FIG Regional Conference,

Indonesia

The Convention on the Elimination of all forms of Discrimination against

women available on

www.un.org/womenwatch/daw/cedaw/text/econvention.htm, accessed on

7-07-06

The Post Newspaper, Mushota urges chiefs to help women acquire land,

Zambia, Wednesday May 10, 2006

UNAIDS (Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS), 2004, 2004 Report on

the Global AIDS Epidemic, Geneva.

UN/ECE, (1996), Land Administration Guidelines, UN publication, Geneva,

1996.

The World Bank, (2005a), Annual report, CD, The World Bank, 1818 H Street

NW, Washington, DC 20433 USA,

www.worldbank.org/gender

The World Bank, ( 2005b) Improving Women’s Lives: World Bank Actions

since Beijing, Washington, DC 20433 USA

Women and law in Southern Africa (WLSA),

www.wlsa.org.zm, accessed on 26th May, 2006

Women and law in Southern Africa (WLSA), (1994), Inheritance in Zambia:

Law and practice, Lusaka, Zambia

Zambia Land Alliance,(2005), Booklet on communities views on the Land

Policy: Draft Land Policy Review Consultation Process in Zambia.

BIOGRAPHICAL NOTES

Ms. Nsemiwe Nsama is currently pursuing a Bachelor of Science

Degree in Real Estate at the Copperbelt University in Zambia. She worked as

an intern at Knight Frank Zambia (Feb – April 2006) and at the Ministry of

Lands (Jan –March 2005). She also worked for Standard Chartered Bank (June

2001 – March 2003) and at Fountain of Hope: An NGO dealing with the welfare

of street children, orphans and other vulnerable children (1999-2001). She

is a member of the Commonwealth Association of Surveying and Land Economy

and also of the African Real Estate Society. She is currently serving as the

vice president of The Copperbelt University Real Estate Students

Association.

CONTACTS

Nsemiwe Nsama

4th Year Real Estate Student

Department of Real Estate Studies School of the Built Environment

The Copperbelt University

PO Box 21692

Kitwe

ZAMBIA

Mobile: + 26096922822

e-mail: nsamansemiwe@lycos.com

|