Article of the Month -

April 2007

|

Integrated Land-Use Management for Sustainable

Development

Prof. Stig ENEMARK, FIG President, Denmark

This article in .pdf-format.

This article in .pdf-format.

SUMMARY

The paper addresses the issue of informal urban development with a

special focus on planning control and integrated land-use management as a

means to prevent and legalise such development.

In this context the paper presents an overall understanding of the land

management paradigm for sustainable development. The paper then identifies

the diversity of planning systems in a European context and the key legal

means of control.

Planning is politics. The framework for political decision-making should

therefore be organised to facilitate an integrated approach to land-use

management that combines the three areas of land policies, land information

management, and land-use management. Such a framework, that includes

monitoring and enforcement procedures, should support sustainable

development, and, at the same time, provide the basic means for preventing

and legalising informal urban development.

1. INTRODUCTION

The paper addresses the issue of informal urban development with a

special focus on planning control and integrated land-use management as a

means to prevent and legalise such development. The Paper is focusing mainly

on the European region.

Today there are about 1 billion slum dwellers in the world, while in 1990

there was about 715 million. UN-Habitat estimates that if the current trends

continue, the slum population will reach 1.4 billion by 2020 if no remedial

action is taken. In 2005 the world´s urban population was about 3.2 billion

out of world total of about 6.5 billion. Current trends predict the number

of urban dwellers will keep rising, reaching almost 5 billion in 2030 where

80% will live in developing countries. Over the next 25 years, the world´s

urban population is expected to grow at an annual rate of almost twice the

growth rate of the world´s total population. (UN-Habitat, 2006).

In this perspective, where one of every three city residents live in

inadequate housing with few or no basic services, it becomes urgent to focus

on informal settlement and find ways and means to influence government

policies and actions. This also relates to the Millennium Development Goal

7, target 11 stating that by 2020 to have improved the lives of least 100

million slum dwellers.

The Millennium Development Goals provide an apt framework for linking the

wealth of cities with increased opportunity and improved quality of life for

their poorest residents. In many countries, however, prosperity has not

benefited urban residents equally. Mounting evidence suggests that economic

growth in itself cannot reduce poverty or opportunities if it is not

accompanied by equitable policies that allow low-income or disadvantaged

groups to benefit from that growth (UN-Habitat, 2006).

In the European region informal urban development do occur to some

extent, especially in Mediterranean countries, even if the scale is much

smaller and also different to the situation in most developing countries.

But, in principle, the problems are the same and relate to factors such as

lack of adequate legal structures; lack of social and economic institutions

for providing and financing low cost housing; lack of updated records and

maps and monitoring procedures; bureaucracy and lack of transparency;

expensive and time consuming procedures for obtaining the relevant permits

and registrations; and political reluctance (Potsiou, 2006).

At the more global scale FIG is committed to the UN-Habitat agenda around

the Global Land Tool Network (GLTN) that aims to facilitate the attainment

of the Millennium Development Goals through improved land management and

tenure tools for poverty alleviation and the improvement of the livelihoods

for the poor.

2. INFORMAL URBAN DEVELOPMENT

Informal urban development may occur in various forms such as squatting

where vacant state-owned or private land is occupied illegally and used for

illegal slum housing; informal subdivisions and illegal construction work

that do not comply with planning regulations such as zoning provisions; and

illegal construction works or extensions on existing legal properties

(Potsiou, 2006).

There is no simple solution to the problem of preventing and legalising

informal urban development. The problem relates mainly to the national level

of economic wealth in combination with the level of social and economic

equity in society, while the solutions relate to the level of consistent

land policies, good governance, and well established institutions.

Land policies may be seen as the set of aims and objectives set by

governments for dealing with land issues. Policy implementation depends on

how access to land and land related opportunities are allocated. Governments

therefore regulate land related activities, including holding rights to

land, controlling the economic aspects of land, and controlling the use of

land and its development. Administration systems surrounding these

regulatory patterns facilitate the implementation of land policy in the

broadest sense, and in well organized systems, they deliver sensible land

management and good governance.

In this regard it is important to understand the dimensions and

implication of land management as a paradigm for dealing with land rights,

restrictions and responsibilities. This is explained in more details in

section 3 below.

It is important to note, however, that where the problem of unauthorised

developments occurs, the particular characteristics of the planning system

may only play a minor part in explaining it. Factors outside the formal

planning system will often play a determining role in its operation and

effectiveness. Factors such as the historical relationship between citizens

and government, attitudes towards land and property ownership, and

implications of social and economics institutions in society will all play a

part amongst other historical and cultural conditions (European Commission,

1997).

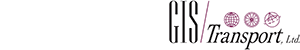

3. UNDERSTANDING THE LAND MANAGEMENT PARADIGM

Land management encompasses all activities associated with the management

of land and natural resources that are required to achieve sustainable

development. The concept of land includes properties and natural resources

and thereby encompasses the total natural and build environment.

The organisational structures for land management differ widely between

countries and regions throughout the world, and reflect local cultural and

judicial settings. The institutional arrangements may change over time to

better support the implementation of land policies and good governance.

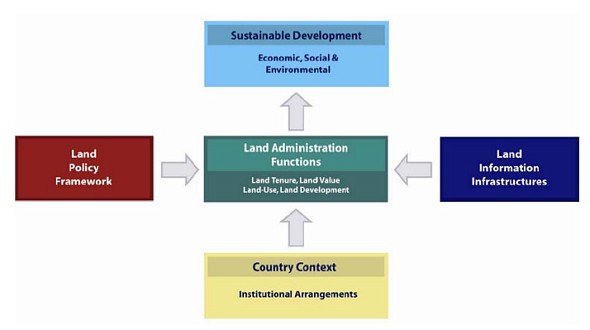

Within this country context, the land management activities may be described

by the three components: Land Policies, Land Information Infrastructures,

and Land Administration Functions in support of Sustainable Development.

This Land Management Paradigm is presented in Figure 1 below (Enemark et

al., 2005):

Figure 1. The land management paradigm

Land policy is part of the national policy on promoting objectives

including economic development, social justice and equity, and political

stability. Land policies may be associated with: security of tenure; land

markets (particularly land transactions and access to credit); real property

taxation; sustainable management and control of land use, natural resources

and the environment; the provision of land for the poor, ethnic minorities

and women; and measures to prevent land speculation and to manage land

disputes.

The operational component of the land management paradigm is the range of

land administration functions that ensure proper management of rights,

restrictions, responsibilities and risks in relation to property, land and

natural resources. These functions include the areas of land tenure

(securing and transferring rights in land and natural resources); land value

(valuation and taxation of land and properties); land use (planning and

control of the use of land and natural resources); and land development

(implementing utilities, infrastructure and construction planning).

The land administration functions are based on and are facilitated by

appropriate land information infrastructures. The land information area

should be organised to combine cadastral and topographic data, and link the

built environment (including legal and social land rights) with the natural

environment (including topographical, environmental and natural resource

issues). Land information should, this way, be organised as a spatial data

infrastructure at national, regional/federal and local levels based on

relevant policies for data sharing, cost recovery, access to data, data

models, and standards.

The four land administration functions (land tenure, land value, land

use, land development) are different in their professional focus, and are

normally undertaken by a mix of professions, including surveyors, engineers,

lawyers, valuers, land economists, planners, and developers. The

interrelations appear through the fact that the actual conceptual, economic

and physical uses of land and properties influence land values. Land value

is also influenced by the possible future use of land as determined through

zoning, land use planning regulations, and permit granting processes. And

the land use planning and policies will, of course, determine and regulate

future land development.

Sound land management is the operational processes of implementing land

policies in comprehensive and sustainable ways. In many countries, however,

there is a tendency to separate land tenure rights from land use rights.

There is then no effective institutional mechanism for linking planning and

land use controls with land values and the operation of the land market.

These problems are often compounded by poor administrative and management

procedures that fail to deliver required services. Investment in new

technology will only go a small way towards solving a much deeper problem;

the failure to treat land and its resources as a coherent whole.

With regard to Europe, and talking about informal urban development,

there is also still some way to go. Many countries in Europe, especially in

the southern and eastern regions, are facing problems in this regard. To

deal with this it is important to understand the cultural diversity within

the European region and also the deriving diversity of planning systems

within the European territory. This is presented in more details in the

following chapter.

4. DIVERSITY OF PLANNING SYSTEMS IN EUROPE

There is no such thing as the common planning system for the European

countries. Planning systems varies considerably in terms of scope, maturity

and completeness, and the distance between expressed objectives and

outcomes. The systems also varies in terms of the locus of power e.g.

centralisation versus decentralisation, and the relative role of the public

and private sector e.g. planning led versus market led approach (European

Commission, 1997).

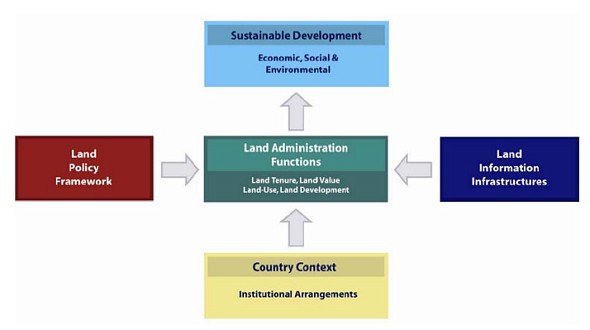

More generally, planning systems are to some extent determined by the

cultural and administrative development of the country or jurisdiction –

just like is the case for cadastral systems. With regard to understanding

the diversity of planning systems there is some merit in having a look at

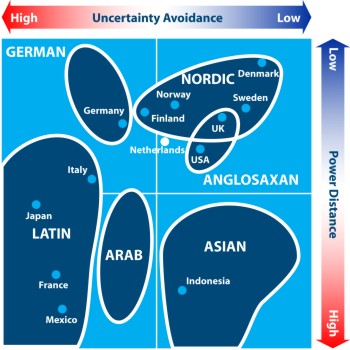

the cultural map of the world as offered by the Dutch sociologist Geert

Hofstede (2001) as shown in figure 2 below.

Figure 2. The cultural map of the world. Adapted form Gert Hofstede,

(2001).

Geert Hofstede divides the world’s cultures into four

squares using the two axes of:

The point is that the issues of uncertainty avoidance and

power distance are both fundamental for the design of planning systems in

any country or jurisdiction. Planning systems therefore varies according

their cultural base. This explains why for example the systems in Nordic and

Latin countries are quite different.

4.1 Traditions of spatial planning

Four major traditions of spatial planning can be identified within the

European countries (European Commission, 1997):

- The regional economic planning approach, where spatial planning is

used as a policy tool to pursue wide social and economic objectives,

especially in relation to disparities in wealth, employment and social

conditions between different regions of the country. Central government

inevitably plays a strong role. France is normally seen as associated

with this approach.

- The comprehensive integrated approach, where spatial planning is

conducted through a systematic and formal hierarchy of plans. These are

organised in a system of framework control, where plans at lower levels

must not contradict planning decisions at higher levels. Denmark and the

Netherlands are associated with this approach. In the Nordic countries

local authorities play a dominant role, while in federal systems such a

Germany the regional government also play a very important role.

- The land use management approach, where planning is a more technical

discipline in relation to the control of chance of use of land. The UK

tradition of “town and country planning” is the main example of this

tradition, where regulation is aiming to ensure the development and

growth is sustainable.

- The Urbanism approach, where the key focus is on the architectural

flavour and urban design. This tradition is significant in the

Mediterranean countries and is exercised through rather rigid zoning and

codes and through a wide range of laws and regulations.

4.2 Operations of planning systems

Another classification can be made in relation to how the systems

operate. Two characteristics can be identified in this regard: the extent of

discretion or flexibility in decision making to allow for development that

is not in line with the adopted planning regulations; and the degree of

unauthorised development e.g. as to whether there is a close, moderate or

distant relation between the stated objectives and the actual development.

By drawing these two categories together, the European countries can be

classified as follows (European Commission 1997):

- The UK has a discretionary system and yet there tends to be a close

relationship between objectives of the system and the actual

development.

- Denmark, Finland, Ireland, and the Netherlands have a moderate

degree of flexibility in decision making, and planning objectives and

policies are close to development that takes place.

- France, Germany, Luxemburg and Sweden all have systems which have

little flexibility in operation, and where development in generally in

conformity with the planning regulations.

- Belgium and Spain both have rather committed systems while there is

only moderate relationship between objectives and reality.

- Finally there is group of countries, Greece, Italy and Portugal,

where the systems are based upon the principle of committed decisions in

plans, but where in practice there has been considerable discrepancy

between the planning objectives and reality.

It must be mentioned, that classifications such as presented above can

only be seen as a very general overview, while, in the details, there may be

all kind of nuances that reflect the specific conditions and cultural

tradition of the individual country.

5. LEGAL MEANS OF PLANNING CONTROL

The relative roles of the public and the private sector refers to the

extent to which the realisation of spatial planning policy is reliant on

public or private sources and the extent to which development might be

characterised as predominantly plan-led or market-led.

The Danish system, for instance, is mainly plan-led and highly

decentralised. The Ministry of the Environment establishes the overall

framework in terms of policies, guidelines and directives. Development

possibilities are determined through the general planning regulations at

local level (municipalities), and further detailed in the legally binding

local/neighbourhood plans. Municipalities are also responsible for granting

of building permits that serve as a final control in the system. Planning at

municipal level is comprehensive and includes determination of land

policies, land use planning, and land use regulations in term of urban/rural

zoning and regulation frameworks for the content of more detailed and

legally binding local/neighbourhood plans that must be provided prior to any

major developments.

The comprehensive municipal plans as well as the local/neighbourhood

plans have to be submitted for public debate and for public inspections and

objections before final adoption. This provides for public participation in

the planning process at all levels. On the other hand, there is no

opportunity for an appeal, inquiry or compensation regarding the contents of

an adopted plan, even the binding local plans. Planning is considered as

politics and the procedures of public participation mentioned above are

regarded as adequate for the legitimacy of the political decision.

However, planning regulations established by the planning system are

mainly restrictive. The system may ensure that undesirable development does

not occur, but the system will not be able to ensure that desirable

development actually happens at the right place and at the right time, as

the planning intentions are mainly realised through private developments.

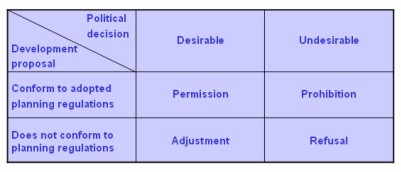

When there is a development proposal which is not in line with the plan,

either a minor departure from the plan may be allowed, or the plan itself

has to be changed prior to implementation. This process includes public

participation, and the development opportunities are finally determined by

the municipal council. On the other hand, development proposals that conform

to the adopted planning regulations are easily implemented without any time

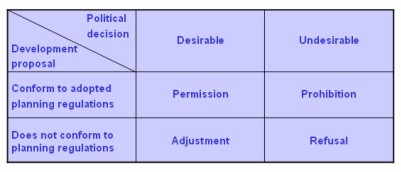

delay. These legal means of planning control are shown in figure 3 below.

Figure 3. The legal means of planning control (Enemark 1999)

5. PLANNING IS POLITICS

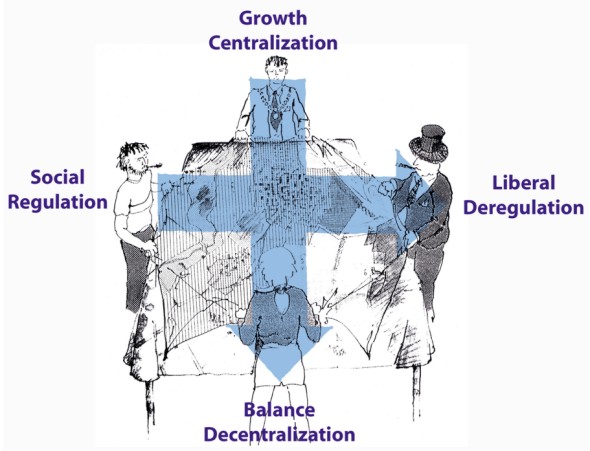

Any planning policy or strategy will have to consider a

number of contradicting professional and political attitudes to development

control such as a social versus a liberal approach, and growth versus a

balanced approach. In planning terms this refers to approaches such as

regulation versus deregulation, and centralization versus decentralization.

This shows that planning is politics. However, to be robust comprehensive

planning must be based on all four approaches and methods of planning in

order to appear as legitimate. This will include a balance between the

functional land-use regulations normally designed by the professional

planner; the demand for control and economic growth that is the traditional

role of the politicians; the wishes for free market investments coming from

the developer; and the often more grass-root based demands articulated by

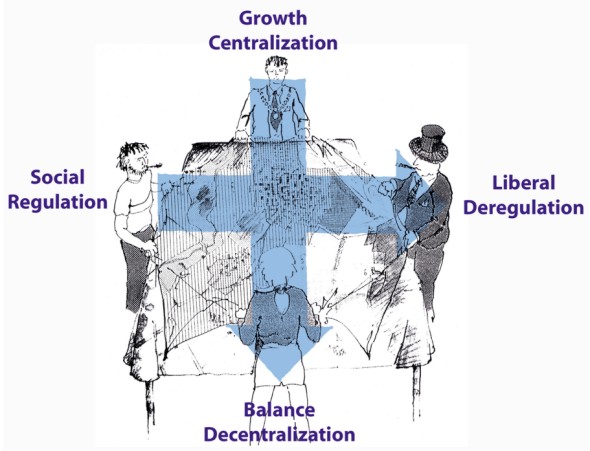

the citizens. The general trends in Europe in terms of the role of the

planning systems are shown in figure 4 below.

Figure 4. The general trends in Europe in terms of the

political attitudes and planning approaches.

6. INTEGRATED LAND-USE MANAGEMENT

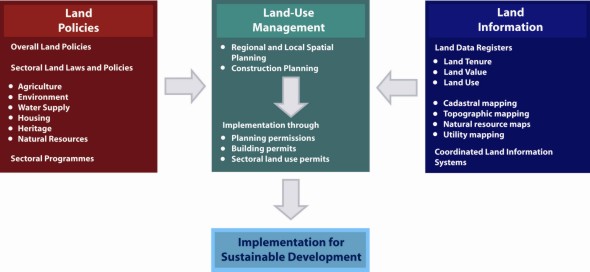

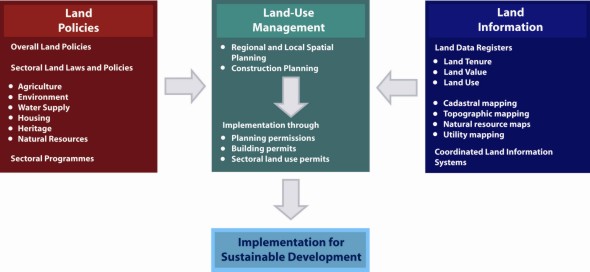

An integrated system of Land-Use Management for Sustainable Development

is shown in figure 5 below.

Integrated land-use management is based on land policies laid down in the

overall land policy laws such as the Cadastral/Land Registration Act; and

The Planning/Building Act. These laws identify the institutional principles

end procedures for the areas of land and property registration, land-use

panning, and land development. More specific land policies are laid down in

the sectoral land laws within areas such as Agriculture, Forestry, Housing,

Natural Resources, Environmental Protection, Water supply, Heritage, etc.

These laws identify the objectives within the various areas and the

institutional arrangements to achieve these objectives through permit

procedures etc. The various areas produce sectoral programmes that include

the collection of relevant information for decision making within each area.

These programmes feed into the comprehensive spatial planning carried out at

national, state/regional and local level.

Figure 5. Integrated land-use management for sustainable

development (Enemark, 2004).

Furthermore, the system of comprehensive planning control is based on

appropriate and updated Land Use Data Systems, such as the Cadastral

Register, the Land Book, the Property Valuation Register, the Building and

Dwelling Register, etc. These registers are organized to form a network of

integrated subsystems connected to the cadastral and topographic maps to

form a national spatial data infrastructure for the natural and built

environment.

In the Land-Use Management System (the Planning Control System) the

various sectoral interests are balanced against the overall development

objectives for a given location and thereby form the basis for regulation of

future land-use through planning permissions, building permits and sectoral

land use permits according to the various land-use laws. These decisions are

based on the relevant land use data and thereby reflect the spatial

consequences for the land as well as the people. In principle it can then be

ensured that implementation will happen in support of sustainable

development.

A global approach to land management, as presented above, depends on

appropriate structures of governance. In this regard, the issue of

decentralisation may be seen as a significant key to achieving the general

aim of sustainable development. In the Nordic setting, and many other places

around the world, the obvious local arena for land-use planning and

decision-making has been the commune - the municipality. It is argued that

whatever outcome may emerge from a decentralised system of decision-making

it must be assumed to be the right decisions in relation to local needs.

Decentralisation thus institutionalises the participation of those affected

by the local decisions. This argument is particularly valid in the area of

land-use decision-making and administration. Land-use planning this way

becomes an integrated part of local politics within the framework of plans

and policies provided at regional and national level. The purpose is to

solve the tasks at the lowest possible level so as to combine responsibility

for decision making with accountability for financial, social, and

environmental consequences.

Another principle in relation to this concept of integrated land-use

management is about comprehensive planning that combines policies and

land-use regulations into one planning document covering the total

jurisdiction. Presentation of political aims and objectives as well as

problems and preconditions, should then justify the land-use planning and

the more detailed land-use regulations. This also relates to public

participation that should serve as a means to create a broader awareness and

understanding of the need for planning regulations and enable a dialogue

between government and citizens around the management of natural resources

and the total urban and rural environment. Eventually, this dialogue should

legitimise the local political decision making. In terms of informal urban

or rural development there is a need for a monitoring system e.g. through

continuing updating of the large scale topographic map base, and proper

enforcement procedures to decide on such development in relation to the

overall land policies.

7. FINAL REMARKS

This paper does not attempt to present an overall global approach to

planning systems and policies in Europe or a comparative analysis of the

maturity or completeness of systems. In fact, the systems can hardly be

compared since the cultural and institutional conditions various throughout

the regions of the European territory – even the terminology and the meaning

of spatial planning vary a lot. Instead, the paper attempts to identify some

general characteristics while the key issue of planning control is discussed

in more details.

The concept of integrated land management is presented as a means to

support sustainable development, and, at the same time, prevent and legalise

informal urban development. The integration of land policies, land

information, and planning control/land-use management should ensure that

land-use decision making is based on relevant policies and supported by

complete and up to date information on land-use and rights in land. This

should also provide for establishing the relevant social and economic

institutions in society in support of legalising the informal sector.

The land management paradigm drives systems dealing with land rights,

restrictions and responsibilities to support sustainable development, and it

facilitates a holistic approach to management of land as the key asset of

any jurisdiction. This represents a huge political challenge. It also

represents a major challenge to the global surveying community that is seen

as the key player in building and running these systems. Understanding the

land management paradigm is the key to building integrated and mature

systems that link policy making, good governance, land administration

systems, and land information infrastructures to form a coherent approach

for dealing with land issues to improve living conditions for all.

Arguably, establishment of such mature systems that are trusted by the

citizens is also the key to preventing and legalising informal urban

development. This goes for, at least, the developed part of the world. In

developing countries this approach must be supplemented by a range of

measures that address the issues of poverty, health, education, economic

growth, and tenure security. This is all included in the perspectives of the

Millennium Development Goals. FIG and the global surveying community will

respond very committed to the MDG´s over the coming years.

REFERENCES

- Alterman, R., (Ed.) (1998): National level Planning in Democratic

Countries – An international comparison of city and regional

policy-making. Liverpool University Press.

- Enemark, S. (1999): Denmark – the EU Compendium of spatial planning

systems and policies. Brussels. ISBN 92-828-2693-7. 124 pp.

- Enemark, S. (2004): Building Land Information Policies. Proceedings

of Special Forum on Building Land Information Policies in the Americas.

Aguascalientes, Mexico, 26-27 October 2004.

http://www.fig.net/pub/mexico/papers_eng/ts2_enemark_eng.pdf

- Enemark, S., Williamson, I., and Wallace, J. (2005): Building Modern

Land Administration Systems in Developed Economies. Journal of Spatial

Science, Perth, Australia, Vol. 50, No. 2, pp 51-68.

- European Commission (1997): The EU compendium of spatial planning

systems and policies. Brussels. ISBN 92-827-9752-X. 192 pp.

- Hofstede, G. (2001): Culture's Consequences: Comparing Values,

Behaviours, Institutions and Organizations Across Nations, 2nd Edition,

Thousand Oaks CA: Sage Publications.

- Potsiou, C. and Ionnidis, C. (2006): Informal Settlements in Greece:

The Mystery of Missing Information and the Difficulty of their

Integration into the Legal framework. Proceedings of the 5th FIG

Regional Conference, Accra, Ghana, March 8-11, 2006, 20 p.

http://www.fig.net/pub/accra/papers/ts03/ts03_04_potsiou_ioannidis.pdf

- UN-Habitat (2006): State of the World´s Cities 2006/7. UN-Habitat,

Nairobi. ISBN: 92/1/131811-4,

http://www.unhabitat.org/pmss/getPage.asp?page=bookView&book=2101

BIOGRAPHICAL NOTES

Stig Enemark is President of the International Federation of

Surveyors, FIG. He is Professor in Land Management and Problem Based

Learning at Aalborg University, Denmark, where he was Head of the School of

Surveying and Planning 1991-2005. He is Master of Science in Surveying,

Planning and Land Management and he obtained his license for cadastral

surveying in 1970. He worked for ten years as a consultant surveyor in

private practice. He was President of the Danish Association of Chartered

Surveyors 2003-2006. He was Chairman of Commission 2 (Professional

Education) of the International Federation of Surveyors (FIG) 1994-98, and

he is an Honorary Member of FIG. He has undertaken consultancies for the

World Bank and the European Union especially in Eastern Europe and Sub

Saharan Africa. He has more than 250 publications to his credit, and he has

presented invited papers to more than 60 international conferences. For

further information and a full list of publications see

http://www.land.aau.dk/~enemark

CONTACTS

Professor Stig Enemark

FIG President

Aalborg University, Department of Development and Planning

Fibigerstrede 11, DK 9220 Aalborg

DENMARK

Tel. +45 9940 8344; Fax + 45 9815 6541

Email: enemark@land.aau.dk

Web site: www.land.aau.dk/~enemark

|